“Set you down this”: A modern Othello and the narrative of racism

TheatreiNQ’s production of Othello (September 2019) reinterprets certain aspects of its eponymous character’s identity to forge a tragedy as topical now as when it was first performed. Alfie Gledhill as Othello is more affable than commanding, but while his youth undermines the gravitas expected of the hero’s position as general it does allow Terri Brabon’s adaptation to sharply comment on contemporary racism. In two fight scenes, Gledhill’s Othello quickly submits when the authorities approach, and is the only character involved in each fracas who does so. Gledhill’s kneeling, submissive posture, with his fingers laced behind his head, is an image undoubtedly familiar to audience members from media coverage of police officers apprehending – sometimes fatally – young black men. Gledhill, along with Rita Neale and Faduma Ali in the ensemble as the only non-“white” cast members, represent the Pacific Islander, indigenous and immigrant peoples othered in contemporary Australian society. The actors and their characters’ positions as outsiders in both Shakespeare’s Venice and Cyprus, and twenty-first century Australia respectively, makes the moments when Gledhill’s general recognises his shared heritage with the slaves all the more affecting.

Image: Rita Neale and Faduma Ali as Cyprus slaves

Othello’s anxieties about his tenuous position in Venice’s racial hierarchy and about Desdemona’s fidelity are depicted in one of the two innovative “dream” sequences, another addition in Terri Brabon’s adaptation. The conflation of these twin fears occurs exactly as Iago intends; Othello internalises the “pestilence” of the villain’s bigotry. Another script change which lends the production greater psychological realism occurs after the attempted assassination of Cassio in Act 5, scene 1 where Iago immediately despatches Roderigo and is only deterred from killing the former lieutenant by the arrival of Lodovico and company.

Psychological realism also underpins the success of Brendan O’Connor’s portrayal of Iago, and TheatreiNQ’s production makes fine use of the villain. At a pre-performance Q&A one of the cast remarked that this production could well have been called Iago, such is that character’s prominence on stage. O’Connor’s rogue literally takes the spotlight (the set lighting operated by Heath Roberts and designed by O’Connor himself) as he delivers his soliloquies; the conceit also serves to temporally separate him from the other cast members, who continue to move in slow-motion while he speaks. The creation of this third space from which Iago addresses his omniscient audience enhances the production’s metatheatricality.

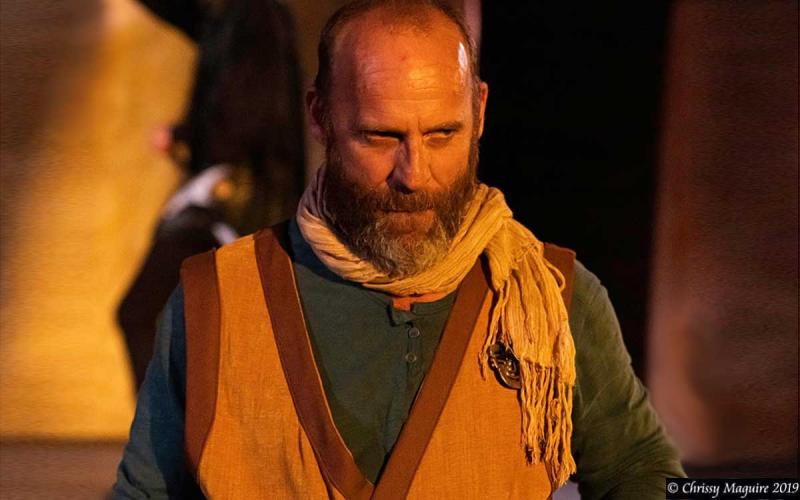

Image: Brendan O'Connor as Iago

O’Connor’s interpretation of Iago reminds one of what can be missed when reading the play: that to succeed, this master manipulator must be all things to all people. O’Connor’s range extends from jovial and witty in his early dealings with Robert Street’s Roderigo (when he exhorts the dupe to “put money in thy purse” [TLN 694-696]) to sympathetic and comforting with Brittany Santariga’s Desdemona after Othello strikes her. The actor’s facility at portraying the many facets of this villain is a revelation of that character’s own acting ability and how his marks are all taken in by “honest Iago” (TLN 1296).

Where the play-text’s Iago pushes the boundaries of the fourth wall by acting as a surrogate storyteller, Brendan O’Connor’s Iago breaks it by addressing the audience directly. Interacting with the front row of the audience – even to the point of physical contact – is a trademark of this versatile actor’s performances in Shakespeare Under The Stars productions, but here he takes it further. At the end of one soliloquy, O’Connor delivers Iago’s scripted lines which refer to himself as a villain, then adds “and you” while facing the audience. Where the original play uses Iago’s soliloquies to imply that the audience are the villain’s accomplices, O’Connor makes this relationship overt as the audience is inducted into his confidence, but does nothing to avert the catastrophe he generates. This addition to the play begs a comparison with the act of spectatorship and inaction which occurs whenever an individual witnesses racial abuse and does nothing, even if the abuse is witnessed from a distance, such as on television. The implication one is left with after watching this performance is that in the act of spectating racial abuse, we all become complicit in its perpetuation. The retention of racist insults in the first scene where Iago awakens Brabantio shows how couching prejudice in comedy is one of the insidious ways racist rhetoric can be used to manipulate. The fact that Brendan O’Connor’s slapstick is genuinely entertaining demonstrates how racial vilification can operate while deflecting attention away from itself.

The production’s examination of racism culminates in Othello’s final speech, which depicts his twin struggles with internalised racism and narrative control, something he knows he will shortly lose:

…I pray you in your letters,

When you shall these unlucky deeds relate,

Speak of me as I am. Nothing extenuate,

Nor set down aught in malice.

Then must you speak

Of one that loved not wisely, but too well;

Of one not easily jealous, but, being wrought,

Perplexed in the extreme; of one whose hand,

Like the base Indian, threw a pearl away

Richer than all his tribe; of one whose subdued eyes,

Albeit unused to the melting mood,

Drops tears as fast as the Arabian trees

Their medicinable gum. Set you down this,

And say besides that in Aleppo once,

Where a malignant and a turbaned Turk

Beat a Venetian and traduced the state,

I took by th'throat the circumcisèd dog

And smote him—thus. (TLN 3650-67)

Othello is both the “turbaned Turk” and the one who kills him; both the Venetian general beaten by Iago, the enemy within, and the one who destroys Desdemona, who represents the Venetian state. It is this dual identity, the product of internalised self-hatred, which renders Othello “perplexed in the extreme”. His request for “nothing extenuate” reflects not only his humility but also a soldier’s insistence on taking full responsibility for mistakes made. However, a just eulogy would mention the extenuating circumstances of his being “wrought”. Nuttall notes that ‘wrought’ is “the old past tense of ‘work’” (2007: 278). Iago has worked upon the Moor by exploiting his insecurities of being a racial and class outsider as a black general and former slave in white, aristocratic Venice. The man who kills Desdemona in a jealous rage is the product of Iago’s sinister ministrations and the second of a possible three Othellos in the play. The first Othello we encounter in the play is the true one; the third will be the product of his auditors as they relate his “unlucky deeds” in letters and reports. Othello, who handles a lynch mob with ease, who knows how to negotiate the world of white, aristocratic Venice, now relies upon his (white) listeners to comprehend the extent of Iago’s effect upon him, a former slave raised to the height of authority in the Venetian army, yet still an outsider. Smith states that:

…knowledge within America’s racial divide is asymmetrical: blacks have always needed to know whiteness, its rules, discipline, and various forms of corporal punishments, while whiteness has been free of the burden of knowing anything about the cultural intimacies of blackness. (2016: 108)

Othello’s privileged, on-stage audience is unlikely to understand the dualities implicit in the Moor’s identity which are given substance in his final speech. Lodovico’s reference to Othello’s having “fallen in the practice of a damned slave” (TLN 3595) likely refers to the term’s usual meaning as a low person, but the presence of actual slavery in the play makes the association between class and worth irresistible, and hence, Lodovico’s own bigotry possible. In a “post-racial” world which declares itself “colour-blind” while ignoring the reality of white privilege and hegemony, it is doubtful whether Othello’s eulogy would render him real or another product of prejudice.

Image: Brittany Santariga and Alfi Gledhill as Desdemona and Othello

During the final moments of the performance O’Connor’s Iago leered at the audience across the grisly tableaux of those he had directly and indirectly killed. The survival of this villain – at least until the play’s end – suggests hatred’s capacity to not only vanquish, but also outlast the virtues of love and loyalty, embodied in the corpses of those lying centre stage. The survival of this representative of the white hegemony also casts doubt on whose narrative will ultimately triumph.

Works Cited

Nuttall, A.D. Shakespeare the Thinker. London: Yale University Press, 2007.

Shakespeare, William. Othello. Edited by Jessica Slights. https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Oth_M/complete/index.html.

Smith, Ian. ‘We are Othello: Speaking of Race in Early Modern Studies.’ Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 67, no. 1, 2016, pp. 104-124.

This review was written by James Cook University student Casey Salt, as part of the university's 'Remaking Shakespeare' subject.